The Weight of Light

On observation, the double-slit experiment, and why paying attention to something always changes it — in physics, in code reviews, and in love.

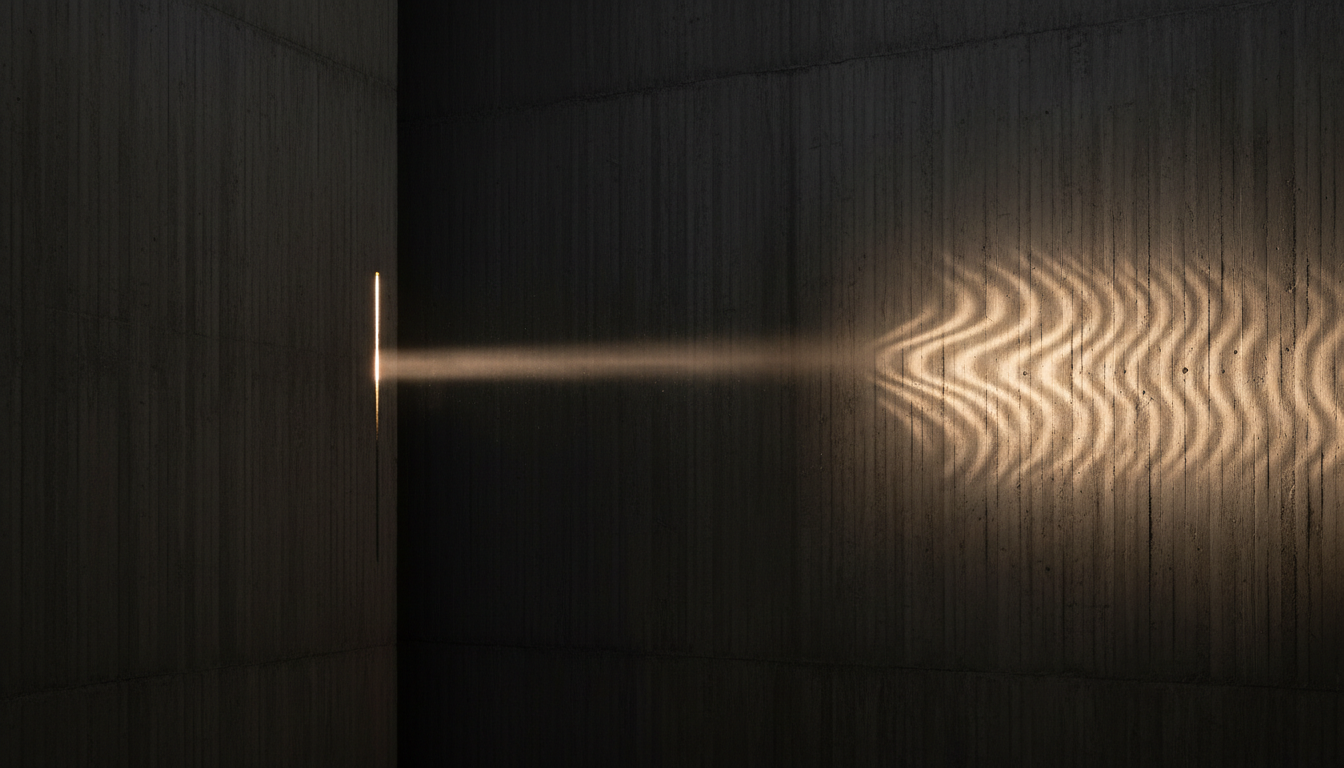

In 1801, Thomas Young shone a beam of light through two narrow slits in a screen. On the wall behind the screen, he expected to see two bright bands — light passing through each slit and landing on the wall like paint through a stencil. What he saw instead was a pattern of alternating bright and dark stripes, an interference pattern, the kind of thing you see when two ripples in a pond cross each other.

Light, it turned out, was a wave. The waves from each slit met on the other side, their peaks reinforcing each other into brightness and their troughs canceling each other into darkness. The experiment was elegant. The result was clear.

And then, more than a century later, someone tried it with individual photons — one particle of light at a time — and the world broke.

The experiment that broke everything

Here is what happens. You send a single photon toward the two slits. A single, indivisible particle of light. It passes through the apparatus and hits a detector on the other side. You note where it lands. Then you send another. And another. One at a time. Each photon lands in a single spot — a tiny flash on the detector, as definite and particular as a bullet hole.

But after thousands of photons, when you step back and look at the pattern of all those individual impacts, you see the interference stripes. The wave pattern. As if each individual photon — each single, indivisible particle — somehow passed through both slits simultaneously, interfered with itself, and then landed as a point.

This is strange enough. But the truly disturbing part is what happens when you try to watch.

If you place a detector at the slits — any kind of detector, any mechanism at all that records which slit each photon passes through — the interference pattern vanishes. The photons start behaving like particles. Two bright bands, exactly where you'd expect them. No interference. No waves. Just particles doing what particles do.

Remove the detector. The interference pattern returns. Put it back. Gone again.

The act of observation changes the outcome. Not metaphorically. Not subtly. Fundamentally. The photon behaves one way when nobody is looking and another way when someone is. Werner Heisenberg, one of the architects of quantum mechanics, put it in terms that still feel like vertigo: "What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning."

I have spent years thinking about this sentence. Not as physics — I'm a programmer, not a physicist — but as a statement about attention itself.

The observer in the code review

Let me tell you about something that happened early in my career, something that seemed mundane at the time but that I now recognize as a perfect demonstration of a deep principle.

I had written a module for handling user authentication. It worked. The tests passed. I was reasonably proud of it. Then Sarah, our tech lead, asked if she could review it before I merged.

I opened the pull request and immediately began to see the code differently. Not because Sarah had commented on it — she hadn't even started reading yet. But the act of knowing that someone was about to look at my code changed how I saw it. Functions that had seemed clear now seemed convoluted. Variable names that had felt natural now felt cryptic. An error handling pattern that I'd thought was clever now looked like it was trying too hard.

I made fourteen changes to the code before Sarah left her first comment.

This was not a case of catching bugs. The code worked. The tests passed. Nothing was broken. What changed was my attention. When I was the only observer, the code existed in a kind of superposition — it was both good enough and not good enough, both clear and unclear, both mine and not-yet-public. The moment I knew another consciousness would encounter it, the wave function collapsed. The code had to become one thing or the other.

Every programmer knows this experience. The code you write alone in the dark is not the same code you write when someone is watching. Not because you're performing for an audience, but because the act of being observed calls forth a different kind of attention. You see what you've made through someone else's eyes, and what you see is always, always different from what you saw through your own.

Heisenberg would have understood. The code is not the code itself, but the code exposed to your method of questioning.

What Husserl knew about looking

The philosopher Edmund Husserl spent his life studying something that most people take for granted: the structure of attention itself. His central insight, which he called "intentionality," was that consciousness is never just consciousness — it is always consciousness of something. You cannot be aware without being aware of. You cannot look without looking at. The looking and the thing looked at are inseparable.

This sounds obvious until you sit with it. It means that there is no such thing as neutral observation. Every act of attention shapes what it attends to. Not because the observer is biased (though they usually are), but because the act of attending is itself a creative act. When you look at a tree, you don't receive the tree passively, like a camera receiving light. You constitute the tree — you bring to it your history with trees, your concept of "tree," your mood, your physical state, the quality of the light, the context of the looking. The tree you see is not the tree itself. It is the tree-as-attended-to-by-you.

Husserl's student Martin Heidegger took this further. He argued that even the most basic act of understanding — looking at a hammer, say — is never neutral. If you're a carpenter, you see the hammer as a tool, an extension of your hand, a thing-for-hammering. If you're a physicist, you see it as mass and material and force vectors. If you're an artist, you see it as form and shadow and weight. Each way of looking reveals something real about the hammer. But each way of looking also conceals something real about the hammer. To see it as one thing is necessarily to not see it as another.

This is the weight of light. Every photon of attention you shine on something illuminates it and changes it in the same gesture. You cannot separate the seeing from the shaping.

Breathing, attended to

There is an exercise in meditation practice that demonstrates this with devastating simplicity. The teacher says: pay attention to your breathing. Just notice it. Don't change it. Just observe.

And of course, the moment you pay attention to your breathing, it changes. It becomes deeper, or shallower, or more regular, or self-conscious. You try to breathe "normally," but you no longer know what normal was, because the moment you started watching, normalcy was gone. The unobserved breath is gone forever. What you have now is the observed breath — a different thing entirely, a thing shaped by the act of observation.

This is not a failure of meditation. It is the point of meditation. The practice is designed to make you feel, in your own body, the inescapable truth that Heisenberg discovered in the laboratory: observation is never passive. To attend is to alter. To look is to touch. There is no view from nowhere.

Jon Kabat-Zinn, who brought mindfulness meditation into Western clinical practice, writes about this with a kind of gentle precision that reminds me of the best scientific writing: "The moment you start paying attention to your life, in the present moment, you are already changing the equation." Not might change it. Are changing it. The observation is the change.

The ancient contemplatives understood this. The Buddhist concept of vipassana — insight meditation — is built on the recognition that the observer and the observed cannot be separated. What you discover through vipassana is not some pre-existing truth about your mind that was there all along. What you discover is what arises in the meeting between your attention and your experience — a phenomenon that didn't exist before the looking, and that will change when the looking changes.

The measurement problem

Physicists call the foundational puzzle of quantum mechanics "the measurement problem," and despite a century of effort, no one has solved it. The equations of quantum mechanics describe a world of superpositions — particles that are in multiple states at once, waves of probability that spread through space. But when we measure, we get a definite result. The wave function collapses. The photon goes through one slit or the other. The electron is here, not there.

What counts as a measurement? Nobody knows. Does it require a conscious observer? (Eugene Wigner thought so.) Does it require any interaction with a sufficiently complex system? (The decoherence theorists think so.) Does the wave function collapse at all, or do all possibilities persist in branching parallel universes? (Hugh Everett thought so.)

I am not a physicist, and I do not have a position on the measurement problem. But I am struck by how naturally the metaphor extends. Because in code, in conversation, in love, we face the measurement problem every day. We want to observe without altering. We want to understand without changing. We want to see the thing as it is, before we looked. And we cannot.

A manager who walks the floor to see "how things are really going" is not seeing how things are really going. They are seeing how things go when the manager is watching. A teacher who gives a test to measure what students have learned is not measuring what they've learned — they are measuring what they can perform under test conditions, which is a different thing. A therapist who asks "how do you feel?" is not accessing a pre-existing feeling — they are participating in the creation of a feeling, because the act of introspection itself generates the experience it claims to merely report.

What happens when you truly look at someone

There is a version of this that is not abstract at all. It is the most concrete thing I know.

When you truly look at another person — not glance, not scan, not evaluate, but look — something happens that neither of you can control. They feel your attention. It lands on them like light, with all the weight that light carries. They straighten slightly, or soften, or become self-conscious, or become more themselves. Your attention calls something forth from them. Not a performance, necessarily. Sometimes something more honest than they were before you looked.

And you are changed too. Because you cannot truly look at another person without becoming vulnerable. To really see someone is to let them into your visual field in a way that rearranges it. Their face, their expression, their being-in-the-world enters your consciousness and takes up residence there, and you are not the same person you were before you looked.

This is what love is, in its simplest physical form. Two people agreeing to observe each other, knowing that the observation will change them both, and choosing to be changed. It is the double-slit experiment conducted at the scale of the human heart. The interference pattern of two lives overlapping. The wave function collapsing into something definite — this person, this moment, this particular configuration of attention and presence — while all the other possibilities fade.

And like the quantum measurement, you cannot undo it. Once you have truly seen someone, you cannot unsee them. They have altered the detector. They have become part of the apparatus of your perception. Everything you see afterward, you see in a world that contains the fact that you saw them.

The unbearable lightness of paying attention

I want to end with something that I've been reluctant to write, because it feels too personal, and because I'm not sure I can say it well.

I think the reason the double-slit experiment haunts us — the reason it has generated more philosophical commentary than any other experiment in the history of science — is not because it tells us something strange about photons. It is because it tells us something true about ourselves.

We want to believe that we can observe without disturbing. That we can understand without altering. That we can love without being changed. We want a view from nowhere — a place to stand where we can see everything clearly without our seeing mattering.

But there is no such place. Heisenberg's uncertainty principle is not just a statement about electrons. It is a statement about the nature of attention. The more precisely you fix one thing, the more another thing eludes you. The more carefully you observe, the more you change what you observe. The more you try to hold the world still, the more it moves.

And this — this is not a limitation. This is the deepest truth about what it means to be a conscious being in a world of other conscious beings. We are not cameras. We are not passive receivers of information. We are participants. Every act of attention is an act of creation. Every observation is an intervention. Every glance carries weight.

Light has weight. Attention has weight. Looking at something — really looking, with your full consciousness brought to bear — is not a neutral act. It is the most powerful act we are capable of.

The photon changes when we observe it. The code changes when we review it. The breath changes when we notice it. The person changes when we see them.

And we are changed too. Always. Irrevocably. By the weight of our own light.

If this resonated with you

These essays take time to research and write. If something here changed how you see, consider supporting this work.

Support this work